Summary: The passcode riddle asks for three three whole positive numbers with each one being equal to or larger than the next. Turns out there are only a handful of numbers this could possibly work for.

Browsing YouTube one morning, I came across the video from TED-Ed and I was intrigued! I’ll be honest, I didn’t get it right away. The clues were…

- The product of three numbers equals some known number (X)

- The sum of those three numbers equals an unknown number

- The last / largest number appears only once in the combination.

Before I start discussing more of the riddle, if you haven’t tried to figure it out, watch the video!

…

…

…

Neat, right?

So I wanted to figure out “How many other numbers are valid in this riddle?” If 36 is okay. What about 38 or 990 or 726,541?

First off, the secret lies in the order of the clues. If all of the products had unique values, we wouldn’t need the third clue.

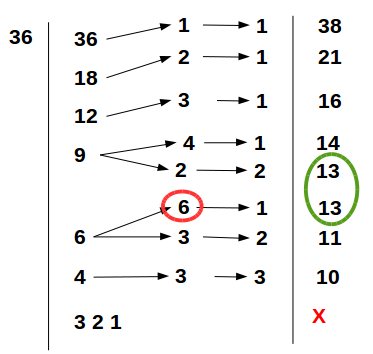

Looking at the number 36, how could we systematically determine if there’s an answer to this riddle?

- Create a list of every factor for your number (X).

- For every factor, multiply it two factors that are less than or equal to the base factor.

- If that vector of factors sums to (X), hold on to it.

- Examine the results

This works for 36 and some other smaller numbers. Here’s roughly what I did.

Now this isn’t too bad, but I didn’t want to waste my time doing this for a big random search of numbers!

Parallel R to the rescue! For those new to parallel processing, take a look at my explanation of parallel processing techniques.

Create a List of Factors for the Input

First, we need to define a way of listing all of our factors. We can use the modulo operator in R, which is number %% divisor. Modulo returns the remainder of number / divisor. If that remainder is zero, we know that “divisor” is a factor of “number”.

listfactors <- function(input){

input_vec = seq(from = input,to = 1, by = -1)

idx <- which((input %% input_vec) == 0)

return(input_vec[idx])

}

- input_vec is a descending list of all the numbers between input (e.g. 36) and 1

- idx pulls out the index of any element that has a zero remainder when being divided by our input (e.g. 36)

Running this for 36, we receive >[1] 36 18 12 9 6 4 3 2 1. Same as in my doodle!

Find Three Numbers Matching the Pattern

Now that we have all of the factors, we need to go through each one and build our three numbers whose product equal some number (e.g. 36). There’s probably a recursive way of doing it, but I created three loops instead.

factortree <-function(input, factors){

factorlen <- length(factors)

factormat <- matrix(data=NA,nrow=0,ncol=5)

colnames(factormat)<-c('f1','f2','f3','rowsum','f1gtg2')

for (f1idx in 1:factorlen){

f1 <- factors[f1idx]

for (f2 in factors[f1idx:factorlen]){

for (f3 in factors[f1idx:factorlen]){

if (all(f1 >= f2, f2 >= f3)){ #Rule #1

if (f1 * f2 * f3 == input){ #Rule #2

lastgt <- as.numeric(f1 > f2) #Rule #3 Indicator

rwsum <- sum(f1,f2,f3)

factormat <- rbind(factormat,c(f1,f2,f3,rwsum,lastgt))

} #End Equivalency IF

} #End >= Constratint

} #End f3 loop

} #End f2 loop

} #End f1 loop

return(factormat)

} #End additionalfactors

The code breaks down to:

- Set up a matrix to start adding data to as we find factors that meet rules one and two.

- Loop through your list of factors.

- Within that first loop, do two more nested loops, but use the first loop’s starting position to reduce the search.

- If rule #1 is met, keep going (in my case, I chose to do the opposite and say each element is in descending order.

- If rule #2 is met create an indicator for rule #3 and add it to the matrix.

Running this code for 36, we get…

> factortree(36,listfactors(36))

f1 f2 f3 rowsum f1gtg2

[1,] 36 1 1 38 1

[2,] 18 2 1 21 1

[3,] 12 3 1 16 1

[4,] 9 4 1 14 1

[5,] 9 2 2 13 1

[6,] 6 6 1 13 0

[7,] 6 3 2 11 1

[8,] 4 3 3 10 1

We can see our two different groups of factors that sum to 13. In addition, we can see that only one of those duplicates has the first factor greater than the second factor.

Identify Which Numbers Meet the Final Rule

Given this matrix, we now have to figure out a way to identify when there is a duplicate and when there is a solution for the passcode riddle.

passcodepossible <- function(input,output=F){

x <- factortree(input,listfactors(input))

rows<-nrow(x) #How many factors

dupevals <- x[duplicated(x[,4]),4]

duperows <- x[x[,4] %in% dupevals,]

if (output){

print(duperows)

}

possible.solutions <- nrow(duperows)

solutions <- sum(duperows[,5])

c(input,rows,possible.solutions, solutions)

}

Essentially, this function is just looking for duplicates, pulling all of those duplicates, and then seeing if those duplicates had any instances of the first factor being greater than the second factor.

1,000 Rounds

Using the foreach and doMC libraries, we can run the following code in parallel. The bigger the number of inputs we try, the more the parallelization pays off.

library(foreach) library(doMC) registerDoMC(2) strt <- proc.time() passcodes<-foreach(i = 1:1000, .combine=rbind) %dopar% passcodepossible(i) dur <- proc.time() - strt dur

The .combine returns the entire dataset as a big matrix. As I increased the number of inputs (e.g. 1:10000 or 1:100000), I noticed a few things.

- There’s an initial setup, where one CPU is running at 100% and your others are dormant.

- There’s a cooldown period where only one CPU is running at 100%.

- I’m assuming that it’s because the one CPU is combining all the data into one output.

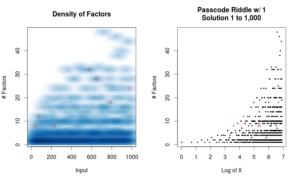

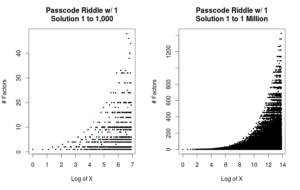

Based on the plot at the top, it’s clear that only a few numbers that meet the rules for the passcode riddle.

1 Million Rounds

Next, I went a bit extreme and decided to see how far I could push my parallel machine. I the numbers one through one million with 10 cores.

This is how much time it took:

> dur

user system elapsed

55956.184 261.556 10550.316

> dur/60/60

user system elapsed

15.54338444 0.07265444 2.93064333

According to the elapsed time, it took nearly three hours for the code to run from start to finish. But the user time is more than three times as large! Looks like my machine pumped out 15 hours of work in three hours. Not bad! Also, my in-memory use jumped to nearly 6.5 Gbs. Don’t try this at home!

For reference, there are only 80 numbers between one and 1 million that would allow you to solve the three rules criteria.

[1] 36 72 225 576 648 784 972 2025 2646 4356 [11] 4500 4608 4900 8281 12348 17496 17600 22500 23409 26244 [21] 27225 28125 28900 30420 36100 36864 38475 42350 47916 57800 [31] 76176 79092 95832 105625 147968 158184 163592 176868 187272 189225 [41] 194579 200900 223587 246016 246924 253125 260091 268912 294912 314721 [51] 342225 388815 403172 438012 438615 472392 475904 480249 489566 493848 [61] 494209 494325 512072 562500 612500 632043 708588 741321 756900 781456 [71] 799552 804609 804972 834632 874225 876024 878004 894916 907578 972196

With a little bit of double checking, the pattern is…

input / f1 = f2**2.

For any given number, the input divided by some factor must equal the second factor squared. The third factor always equals the second factor.

Bottom Line: The passcode riddle is an interesting logical puzzle but have very few possible solutions. However, using parallel computing we can find those solutions in short order.